Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder in which the normal chemical and electrical activities between nerve cells in the brain (neurons) become disturbed. This disturbance causes the neurons to fire abnormally, resulting in seizures.

Generalized Seizures

People having a generalized seizure are generally not aware of their surroundings, so observers should try to be alert to the person’s safety.

Some types of generalized seizures include:

- Absence seizures Previously known as “petit mal” seizures, absence seizures are more common in children. This type of seizure may last only seconds and is sometimes confused with daydreaming. The person is usually unresponsive, but people having an “atypical” absence seizure may be able to respond a little.

- Atonic seizures These are also known as “drop attacks” or “drop seizures.” The person’s normal resting muscle tension (called “tone”) goes limp. If the person is sitting, they may suddenly slump over. If they are standing, they may drop like a rag doll to the ground.

- Myoclonic seizures These seizures are sudden body “jolts” or increases in muscle tone that make it seem as if the person has been jolted with electricity. A myoclonic seizure is similar to the sudden jerks people often experience as they are falling asleep, but these latter “sleep myoclonic” jerks are harmless, while myoclonic seizures aren’t. A subtype of myoclonic seizures, infantile spasms, typically begin in children between 3 and 12 months old and may persist for several years. They typically consist of a sudden jerk followed by stiffening. This particularly severe form of epilepsy can have lasting effects on a child.

- Tonic seizures In this kind of seizure, the person’s muscle tone suddenly stiffens and they lose consciousness. They may also fall to the ground, but they fall in a rigid manner, more like a tree trunk than a rag doll.

- Clonic seizures This type of seizure causes a person’s muscles to spasm and jerk; the muscles in the elbows, legs, and neck flex and relax in rapid succession. The jerking motion slows down as the seizure subsides and finally stops altogether.

- Tonic-clonic seizures Previously known as “grand mal” seizures, these are the kind of convulsions that people often associate with epilepsy. The person becomes rigid, as with a tonic seizure, and then muscle jerking (known as “clonus”) begins.

If you see a person having an apparent seizure of any kind, do what you can to ensure the person’s safety, and make note of the time. Tonic-clonic seizures lasting more than 5 minutes are considered to be a medical emergency, and you should call 911 if you observe one.

People having a tonic-clonic seizure may lose control of their bladder or bowels, and they will feel exhausted and sore after the seizure (known as the “postictal” period).

Focal Seizures

Many focal epilepsies have an “aura,” or warning symptoms of an upcoming seizure. The person experiencing the aura is conscious.

Focal seizure symptoms are subdivided into motor (movement), sensory, autonomic, and psychic.

A focal seizure with motor symptoms typically causes jerking movements of a foot, the face, an arm, or another part of the body, while a focal seizure with sensory symptoms affects a person’s hearing or sense of smell or may cause them to experience hallucinations.

A focal seizure with autonomic symptoms affects the part of the brain responsible for involuntary functions, causing changes in blood pressure, heart rate, or bowel or bladder function. Finally, focal seizures can strike the parts of the brain that trigger emotions or memories, causing feelings of fear, anxiety, or déjà vu (the feeling that something has been experienced before).

Because focal seizures only involve part of the brain, symptoms are often not as extensive as generalized seizures. Focal symptoms often involve only one side of the body instead of both.

Focal seizures are further classified by level of awareness: aware, impaired awareness, or unknown awareness.

- Focal aware seizure (previously called “simple partial”) During a focal aware seizure, the person is awake, and they will be able to recall the seizure afterward. They may be “frozen” and unable to respond, or they may be able to tell you what is happening. These seizures may last from a few seconds to a couple of minutes, and the person will usually be able to resume normal activity afterward, although a focal aware seizure may sometimes be a sign that a more severe seizure is still to come.

- Focal impaired awareness seizure (previously called “complex partial”) During this kind of seizure, there may be slightly impaired awareness, or awareness may be severely impaired. The person having the seizure may perform activities that seem purposeful, but it’s as if there’s “nobody home.” The actions can be fairly simple, like lip-smacking, or they may be complex actions, like walking, removing clothing, thrusting the pelvis, or bicycling the legs. They may seem like they are daydreaming, but they can’t be startled out of it, unlike a person who is daydreaming.

Some seizures start as a focal impaired awareness seizure and then progress to a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Remember, any tonic-clonic seizure lasting over five minutes should prompt a call to 911.

Combined and Unknown Seizure Types

Learn More About Dravet Syndrome

Learn More About Signs and Symptoms of Epilepsy

Types of Epilepsy

Epilepsies are often grouped by a complex set of characteristics that mark a type as a known “syndrome.” They are also sometimes described by their symptoms or by the part of the brain affected.

Examples of Some Epilepsy Syndromes

Here are some of the most common epilepsy syndromes:

- Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE) People with this epilepsy syndrome have staring spells that last 10 to 20 seconds and then end abruptly. This was previously called “petit mal” epilepsy and is most common in children. CAE often responds to medical treatment and disappears by adolescence.

- Juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE) JAE is different from childhood absence epilepsy (CAE). The seizures tend to last longer, and the person may have this epilepsy for the rest of their life. About 80 percent of people with JAE will also have tonic-clonic seizures. JAE will often respond to treatment, but that treatment tends to be lifelong.

- Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) Usually seizures take place within an hour of awakening. People with JME can have absence seizures, myoclonic (muscle-jerking) seizures, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Common triggers include sleep deprivation and stress, or exhaustion after excessive alcohol intake.

- Childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, previously known as benign rolandic epilepsy This is a focal seizure type that appears in children ages 3 to 12 years. Half of the face may begin to twitch, and numbness of the face or tongue can occur. These seizures usually occur at night, often during sleep. For most children, seizures cease by age 13, although they can continue to age 18.

- Reflex epilepsies With reflex epilepsy syndromes, a certain stimulus can trigger a generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure. The most common reflex epilepsy syndrome is photosensitive epilepsy, where flashing lights can trigger a seizure. This can make it a problem to watch TV, play video games, or even observe light through the trees. Other reflex epilepsy triggers can be auditory, like a song or church bells. Some people have tactile triggers, such as a hot bath or toothbrushing. The best way to prevent a seizure is to avoid the trigger, but that is not always possible.

- Sleep-related epilepsy syndromes Some epilepsies relate directly to sleep or to immediate arousal from sleep. Examples include sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy (SHE; previously known as nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy) and nocturnal temporal lobe epilepsy (NTLE). As with childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, sleep-related epilepsy syndromes are sometimes not caught unless someone has a seizure with motor symptoms in their sleep.

Characteristics of Epilepsies Based Upon Brain Region

Because different parts of the brain perform different functions, seizure activities in different areas can have distinct symptoms.

Here are some examples of epilepsy syndromes characterized by the regions of the brain that are affected:

- Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) TLE often has an aura of déjà vu, fear, or an unusual smell or taste. TLE often begins in childhood or in the teen years. A TLE seizure can look like a staring spell, or the person may engage in pointless repetitive behaviors, called automatisms. Some common automatisms include picking at clothing, smacking the lips, eye blinking, and unusual head movements. TLE is associated with damage to the hippocampus, called hippocampal sclerosis (HS). Damage to the hippocampus can also interfere with learning and memory.

- Frontal lobe epilepsy This often affects movement. A person who has frontal lobe epilepsy may have muscle weakness and abnormal movements, like twisting, waving the arms and legs, or grimacing during seizures. The person may be startled and even scream. There is often some loss of awareness, and some frontal lobe seizures happen when the person is asleep.

- Neocortical epilepsy This type of epilepsy can be generalized or focal. The cortex is the outer layer of the brain, and seizure symptoms can vary from unusual sensations to visual hallucinations, emotional changes, or convulsions.

- Occipital lobe epilepsy This is uncommon but can develop because of tumors or brain malformations, and is one of the benign focal epilepsies of childhood. It sometimes causes convulsions on both sides of the body, and visual changes can occur both before and after the seizure.

- Hypothalamic seizures This rare type of epilepsy begins in childhood and is caused by a noncancerous tumor of the hypothalamus, a region at the base of the brain. Hypothalamic hamartoma is often difficult to diagnose, as the seizures can seem like laughing (“gelastic” seizures) or crying (“dacrystic” seizure).

How Is Epilepsy Diagnosed?

A variety of tests are used to look for evidence of epilepsy and to rule out other possible causes of seizures.

Sometimes brain imaging is done using MRI or computed tomography (CT) to look for structural abnormalities in the brain that may be causing seizures.

A person’s medical history also provides important clues to the underlying cause of seizures.

Learn More About Diagnosing Epilepsy

Prognosis of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a potentially life-threatening condition, and it carries a risk of premature death if it’s not properly diagnosed and treated.

Children and young adults diagnosed with the condition — roughly half of all cases of epilepsy are diagnosed in people age 25 years or younger — aren’t likely to see any reduction in their life expectancy from epilepsy, particularly if they’re on a medication that effectively controls their seizures.

Treatment and Medication Options for Epilepsy

The first type of treatment usually offered for epilepsy is antiseizure medication (ASM), of which there are more than 20. Typically, antiseizure drugs are started at a low dose, and the dosage is gradually increased to find the proper dose for the person.

Medication Options

Most people with epilepsy can become seizure-free by taking an antiseizure medication. Some may need to take a combination of ASMs to control their seizures.

Finding the right medication and dose can be difficult. In helping you find the right ASM, your doctor will consider your condition, the frequency of your seizures, your age, and any other health conditions you may have, as well as any medications you may be taking for them.

To start, your doctor will prescribe a single medication at a relatively low dose, increasing the dose gradually until your seizures are controlled.

ASMs do have several side effects. Among the most common, mild side effects are:

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Weight gain

- Loss of bone density (osteoporosis)

- Rashes

- Balance and coordination difficulties

- Speech problems

- Memory loss

- Trouble concentrating

More serious, but rare, side effects include:

- Depression

- Thoughts of suicide

- Severe rash

- Inflammation of the liver

To get the most from your drug treatment — and to maximize control of your seizures — you should take medications as prescribed and call your doctor before switching to a generic version of your medication or taking other prescription medications, over-the-counter drugs, or herbal remedies for your epilepsy or other health problems.

Don’t discontinue your ASM without talking to your doctor, and contact your doctor as soon as possible if you experience feelings of depression, suicidal thoughts, or unusual changes in your mood or behaviors.

Medical Marijuana and CBD

In June 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug Epidiolex (cannabidiol), which is derived from the cannabis plant, for the treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome.

Epidiolex is made from purified cannabidiol (CBD), an ingredient found in marijuana. The medication does not contain THC, the primary psychoactive component in marijuana that causes the “high” associated with its use.

Epidiolex has been found to reduce seizure frequency in children and young adults with these epilepsy syndromes.

Surgery for Epilepsy

More than half of those newly diagnosed with epilepsy will become seizure-free with their first medication. If anti-epileptic medications don’t work, your doctor may recommend surgery.

Surgery can be beneficial if scans of your brain reveal that your seizures originate in a small, well-defined area of your brain, and its removal won’t interfere with speech, language, motor function, vision, or hearing.

In most epilepsy surgeries, the neurosurgeon removes the area of your brain causing your seizures. Traditional surgery requires opening up the skull to access the part of the brain to be removed. A newer type of surgery, called stereotactic laser ablation, can be done through a small hole in the skull. “Stereotactic” refers to the use of medical imaging technologies that allow the surgeon to precisely place a medical instrument in the brain.

In stereotactic laser ablation, the surgeon uses CT or MRI images to guide a laser through the brain to the cells causing the seizure. The laser is then used to burn, or “ablate,” these cells.

Even after successful surgery, some people may need to continue taking an antiseizure medication to prevent seizures, but they may be able to take fewer drugs at reduced doses.

Neurostimulation Options

An alternative to surgery for some people with epilepsy is neurostimulation, in which either the vagus nerve or parts of the brain are stimulated with electrical pulses to stop seizures and possibly prevent them.

Ongoing research suggests that long-term use of the device may also reduce the likelihood of seizures occurring in the first place.

Continuous stimulation Researchers are also experimenting with a technique called continuous stimulation. In this approach, an electrical charge is applied to the seizure onset zone, or the area of the brain where seizures originate, to interrupt them.

Alternative and Complementary Therapies

Some people with epilepsy try alternative and complementary therapies, including:

- Acupuncture

- Vitamin E

- Herbal remedies

- Stress-relief techniques

- Specialty diets

Although the research supporting the effectiveness of these approaches is limited, some people say they have helped them manage their seizures.

Although most herbal supplements are generally safe, some can make your seizures worse, cause side effects, or affect how your epilepsy medicines work. Talk to your doctor before taking any herbal supplement.

Depending on what triggers your seizures, stress reduction may help limit their frequency — and help improve your overall health and sense of well-being at the same time.

Physical activity such as walking, swimming, or bike riding has been shown to help people with epilepsy, as exercise also calms the abnormal electrical brain activity that triggers seizures. Talk to your doctor before starting a new exercise program to make sure it’s right for you and your epilepsy.

In general, you should avoid activities that could be dangerous if you have a seizure — like skiing. And, if you’re out and about exercising, be sure to wear a medical alert bracelet, just in case you have a seizure.

Yoga can also help reduce stress, as it combines exercise with deep breathing and meditation to strengthen your body and calm your mind.

Meditation can redirect your mind away from stress and the specific thoughts causing it. In particular, mindfulness meditation may help reduce seizures and improve mood in people with epilepsy.

Music therapy may help children with epilepsy. In the 1990s, researchers discovered that children with epilepsy had less abnormal brain activity and fewer seizures when they listened to a Mozart sonata called K448. This is referred to as the Mozart effect.

But some forms of music may trigger seizures, so talk to your doctor before experimenting with music therapy for yourself or your child.

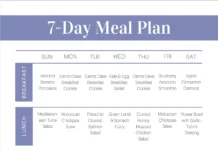

Finally, the so-called keto diet — a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet — has been shown to control seizures in some people with epilepsy, according to the Epilepsy Foundation. You shouldn’t start the diet on your own — it must be prescribed by your doctor and monitored by a dietitian, because it requires careful measurement of calorie, fluid, and protein intake.

The diet has proved most effective in children with seizures that don’t respond to antiseizure medications, the Epilepsy Foundation says.

Its full name is the ketogenic diet, because it causes your body to produce ketones, or acids that are formed when the body uses fat for its source of energy. Higher blood ketone levels are believed to lead to improved seizure control.

Learn More About Treatment for Epilepsy: Medication, Alternative and Complementary Therapies, Surgery Options, and More

Prevention of Epilepsy and Seizures

An infection called cysticercosis is thought to be the most common cause of epilepsy, and it’s transmitted to humans from a parasite, the CDC says. You can reduce your risk of infection by practicing good personal hygiene — such as washing your hands regularly — and using safe food preparation practices, including regularly cleaning surfaces in your kitchen.

Another common cause of epilepsy is traumatic brain or head injuries. Of course, you can’t prevent all accidents, but you can reduce your risk for head injuries by wearing a helmet when playing sports such as hockey or when riding a skateboard or bicycle, for example.

Wearing seatbelts while riding in the car and making sure to use child safety seats for babies and younger children can also help.

Reducing your risk of heart attack and stroke can also help lower your risk of developing epilepsy later in life, as some epilepsies are caused by these serious health events. Following a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and reducing stress can help you maintain heart and blood vessel health.

Finally, some epilepsies have been linked with complications during pregnancy and childbirth, according to the CDC. Developing a prenatal care plan with your doctor can minimize the risks to your newborns.

Once you’ve been diagnosed with epilepsy, the best way to prevent seizures, and reduce their frequency, is to stick with the treatment prescribed by your doctor. If you feel your treatment isn’t working, and seizures are affecting your quality of life, talk to your doctor about other options.

A product that can help adults and children age 6 and older is the Embrace2, a sort of smartwatch for epilepsy that senses electrodermal activity — variations of the electrical conductance of the skin in response to sweating — and physical motion that may indicate a seizure. The device can be programed to send an alert to a caregiver via smartphone when it senses signs of a likely seizure, so that the wearer is not alone when a seizure happens.

Research and Statistics: How Many People Have Epilepsy?

Researchers are studying many potential new treatments for epilepsy, as well as refinements and new applications for existing treatments.

Related Conditions

Epilepsy may increase a child’s risk for a mood disorder, such as depression, or a learning disorder, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), according to the Epilepsy Foundation.

Children with epilepsy may also experience more headaches, including headache caused by migraine.

Individual risk for these related conditions — or comorbidities — varies, and depends on a number of factors, including how often the child has seizures, how much (and which) medication the child is taking, and the child’s age when seizures started.

Depression is thought to be the most common comorbidity with epilepsy, as it affects some one in four children with the condition, according to the Epilepsy Foundation. Depression is a serious condition, and it can lead to thoughts of suicide.

Depression is treatable, either through cognitive behavioral therapy, medication, or the two in combination.

In addition to depression, people with epilepsy are more likely to have anxiety disorder and bipolar disorder, research suggests. Although the links between bipolar disorder and epilepsy remain unclear, it’s likely that worries over seizures may contribute to feelings of anxiety.

If you or your child is experiencing anxiety, talk to your doctor.

As many as one-third of all children with epilepsy show the signs or symptoms of ADHD, the Epilepsy Foundation says. Most children with epilepsy and ADHD have difficulty paying attention or focusing, rather than being hyperactive.

Resources We Love

From patient advocacy organizations to informational sites to social networks, there’s help and support out there for individuals with epilepsy and their families and caregivers.

Epilepsy Foundation

The Epilepsy Foundation has comprehensive information about epilepsy and about living with epilepsy, including finding an epilepsy specialist.

MyEpilepsyTeam

Ask questions about epilepsy or just get to know others living with it on this online social network.

Mayo Clinic

For understandable information on epilepsy, the Mayo Clinic website is a great place to start.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

The NINDS “Hope Through Research” page features in-depth information about epilepsy as well as updates on NINDS-supported research on epilepsy and its treatment.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC provides basic information about epilepsy as well as links to the Managing Epilepsy Well network and to CDC programs focused on epilepsy.

Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE)

CURE raises money and awards grants to fund epilepsy research.

KidsHealth

KidsHealth from Nemours has epilepsy information geared toward kids, as well as separate articles for teens, and parents, in Spanish as well as English.

Learn More About Resources for Epilepsy

Additional reporting by Brian P. Dunleavy.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

- The Epilepsies and Seizures: Hope Through Research. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. June 26, 2020.

- Epilepsy Data and Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 30, 2020.

- Generalized Seizures. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Focal Seizures. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Focal Epilepsy. Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- Focal Seizures. Epilepsy Action. November 2019.

- Types of Epilepsy & Seizure Disorders in Children. NYU Langone Health.

- Focal to Bilateral Tonic-Clonic Seizures. Epilepsy Foundation of New England.

- Unknown Onset Seizures. Epilepsy Foundation of New England

- Childhood Absence Epilepsy. Epilepsy Foundation. January 19, 2020.

- Juvenile Absence Epilepsy. Epilepsy Foundation. January 19, 2020.

- Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy. Epilepsy Foundation. March 12, 2019.

- Childhood Epilepsy With Centrotemporal Spikes. International League Against Epilepsy. March 30, 2020.

- Reflex Epilepsies. Epilepsy Foundation. September 10, 2019.

- Sleep-Related Hypermotor Epilepsy (SHE). Epilepsy Foundation. November 19, 2019.

- Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE). Epilepsy Foundation. August 26, 2019.

- Frontal Lobe Seizures. Mayo Clinic. June 25, 2019.

- About Neocortical Epilepsy. Columbia Neurological Surgery.

- Occipital Lobe Epilepsy. UWHealth.

- Hypothalamic Hamartoma. Epilepsy Foundation. March 3, 2017.

- Facts and Figures. American Epilepsy Society.

- Epilepsies by Etiology. International League Against Epilepsy. March 30, 2020.

- Epilepsy: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clinic. May 5, 2020.

- Granbichler CA, Zimmermann G, Oberaigner W, et al. Potential Years Lost and Life Expectancy in Adults With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy. Epilepsia. September 28, 2017.

- Sen A, Jette N, Husain M, et al. Epilepsy in Older People. The Lancet. February 29, 2020.

- Will I Always Have Seizures? Epilepsy Foundation. March 19, 2014.

- Geerts A, Arts WF, Stroink H, et al. Course and Outcome of Childhood Epilepsy: A 15-Year Follow-Up of the Dutch Study of Epilepsy in Childhood. Epilepsia. July 2010.

- Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, et al. Two-Year Remission and Subsequent Relapse in Children With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy. Epilepsia. December 2001.

- Abu-Sawwa R, Scutt B, Park Y. Emerging Use of Epidiolex (Cannabidiol) in Epilepsy. Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS). Epilepsy Foundation. March 12, 2018.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). Epilepsy Foundation. September 15, 2018.

- Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS). Epilepsy Foundation. November 18, 2017.

- What Is Responsive Neurostimulation? Epilepsy Foundation. April 23, 2019.

- Chen S, Wang S, Rong P, et al. Acupuncture for Refractory Epilepsy: Role of Thalamus. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014.

- Mehvari J, Motlagh FG, Najafi M, et al. Effects of Vitamin E on Seizure Frequency, Electroencephalogram Findings, and Oxidative Stress Status of Refractory Epileptic Patients. Advanced Biomedical Research. March 16, 2016.

- Liu W, Ge T, Pan Z, et al. The Effects of Herbal Medicine on Epilepsy. Oncotarget. July 18, 2017.

- Ketogenic Diet. Epilepsy Foundation. October 25, 2017.

- Preventing Epilepsy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 30, 2020.

- Stereotactic Laser Ablation for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (SLATE). ClinicalTrials.gov. September 7, 2020.

- Quigg M, Barbaro NM. Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Treatment of Epilepsy. Neurological Review. February 2008.

- McGonigal A, Sahgal A, De Salles A, et al. Radiosurgery for Epilepsy: Systematic Review and International Stereotactic Radiosurgery Society (ISRS) Practice guideline. Epilepsy Research. November 2017.

- Proctor C, Slézia A, Kaszas A, et al. Electrophoretic Drug delivery for seizure control. Science Advances. August 29, 2018.

- Gil-López F, Boget T, Manzanares I, et al. External Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation for Drug Resistant Epilepsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Stimulation. September–October 2020.

- Yang J, Phi JH. The Present and Future of Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. May 2019.

- QuickStats: Age-Adjusted Percentages of Adults Aged ≥18 Years Who Have Epilepsy, by Epilepsy Status and Race/Ethnicity — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2010 and 2013 Combined. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016.

- Szaflarski M, Szaflarski JP, Privitera MD, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Treatment of Epilepsy: What Do We Know? What Do We Need to Know? Epilepsy & Behavior. September 1, 2006.

- Researchers Find Racial Disparities in Care for Epilepsy at Hospitals. NeurologyToday.

- Related Conditions. Epilepsy Foundation. March 19, 2014.

- Types of Epilepsy Syndromes. Epilepsy Foundation. September 3, 2013.